The Backstory: What our reporters saw, heard and learned at the Portland protests

opinion

Nicole Carroll USA TODAY

Published 9:49 AM EDT Jul 31, 2020

I'm USA TODAY editor-in-chief Nicole Carroll, and this is The Backstory, insights into our biggest stories of the week. If you'd like to get The Backstory in your inbox every week, sign up here.

Trevor Hughes spent last week in Portland, Oregon, covering the growing unrest. He joined reporter Lindsay Schnell, who grew up near Portland and has been based there for the past nine years, to cover the protests.

I wanted to hear from both of them. I had questions.

What don't we see? What don't we hear enough about?

"The thing to bear in mind is that, especially for this most immediate period of time, the protest is only immediately surrounding the federal courthouse," Hughes said. "And so it wasn't like people were wandering the streets setting buildings on fire. This was very, very limited to a couple of blocks right around the courthouse."

The protests intensified after President Donald Trump deployed more than 100 federal law enforcement agents to Portland, saying the agents were there to protect federal property. Local officials and critics accused the president of creating more conflict during nationwide protests over racial injustice and police brutality against Black Americans. On Wednesday, local and federal officials announced an agreement to begin withdrawing the federal agents.

Were the protests mostly peaceful? Were they violent?

Both, Hughes said.

"You had people showing up with baseball bats. We had people try to tear down the security fence around the courthouse. They tore the security cameras off the buildings. They tried to break the windows. When law enforcement responded with the tear gas, for instance, the crowd would pick up those tear gas canisters and throw them back at the police officers."

But, he said, "The vast majority of people there were being peaceful, exercising their constitutional rights in a very polite way. But those large crowds allowed a small number of people the cover necessary to shoot fireworks from the darkness, to throw glass bottles."

And the response? Hughes only saw tear gas and pepper spray deployed, but others reported less-lethal ammunition such as rubber bullets being used.

How did it get so heated?

Schnell said protesting is part of Portland. "One thing about this city is that we love to protest and in a lot of ways, I think we're pretty angsty. If you live here, it's easy to let the protesting kind of fade into the background. We're always protesting something. But when the feds showed up, suddenly it renewed people's energy."

She said her city is passionate and the protests against inequality have hit home, in part because of the makeup of the city. Portland's population is 77% white and 6% Black, equating to about 40,000 Black people in the city.

"I think part of it is we recognize our city is painfully white and has a really racist history within our city and within our state," she said. "There's an attitude among Portlanders that, you know what, so many times we've just let it fade to the background and we can't do that anymore."

She was also struck by how young some of the activists were. Too young to vote, but out on the streets night after night. "They're coming together and saying we can create change. And I think we are seeing that more and more across the country."

Another storyline emerged as well. Activists worried the violence was overshadowing the message of Black Lives Matter protesters.

Edreece Phillips, 48, had been protesting for weeks. He told Hughes he'd been keeping people off the courthouse fence. He talked to federal agents, who told him if the protesters stayed back, they'd stay inside the courthouse.

“They don’t come out unless we try to get in," Phillips told Hughes. "All that stuff people are doing is making it so that Black voices are being heard less and less and less.”

He kept an eye on the courthouse. At one point, as protesters were getting closer, Hughes reported Phillips "snatched a sign from a young man and stomped on it."

"I am sick of you doing this," Phillips yelled to the protester, dressed in all black. "I have warned you already. I'm sick of it."

He told Hughes he saw small groups of white protesters aligned with the Black Lives Matter movement throw water bottles at the federal court building, shoot fireworks and shake the fence.

“A lot of the people who are doing it are not Black. They throw s--- and start s--- and run away and yell 'Black Lives Matter,' and then go home and take off their clothes. But I can’t take off my black," Phillips said. "And the more damage they do to this building – well, everyone thinks it’s people of color doing all this and it’s not. “

It was important for us to report from Portland, to stand at the courthouse fence, to watch both law enforcement and the protesters, to find the stories behind the stories. Even if it meant being in harm's way.

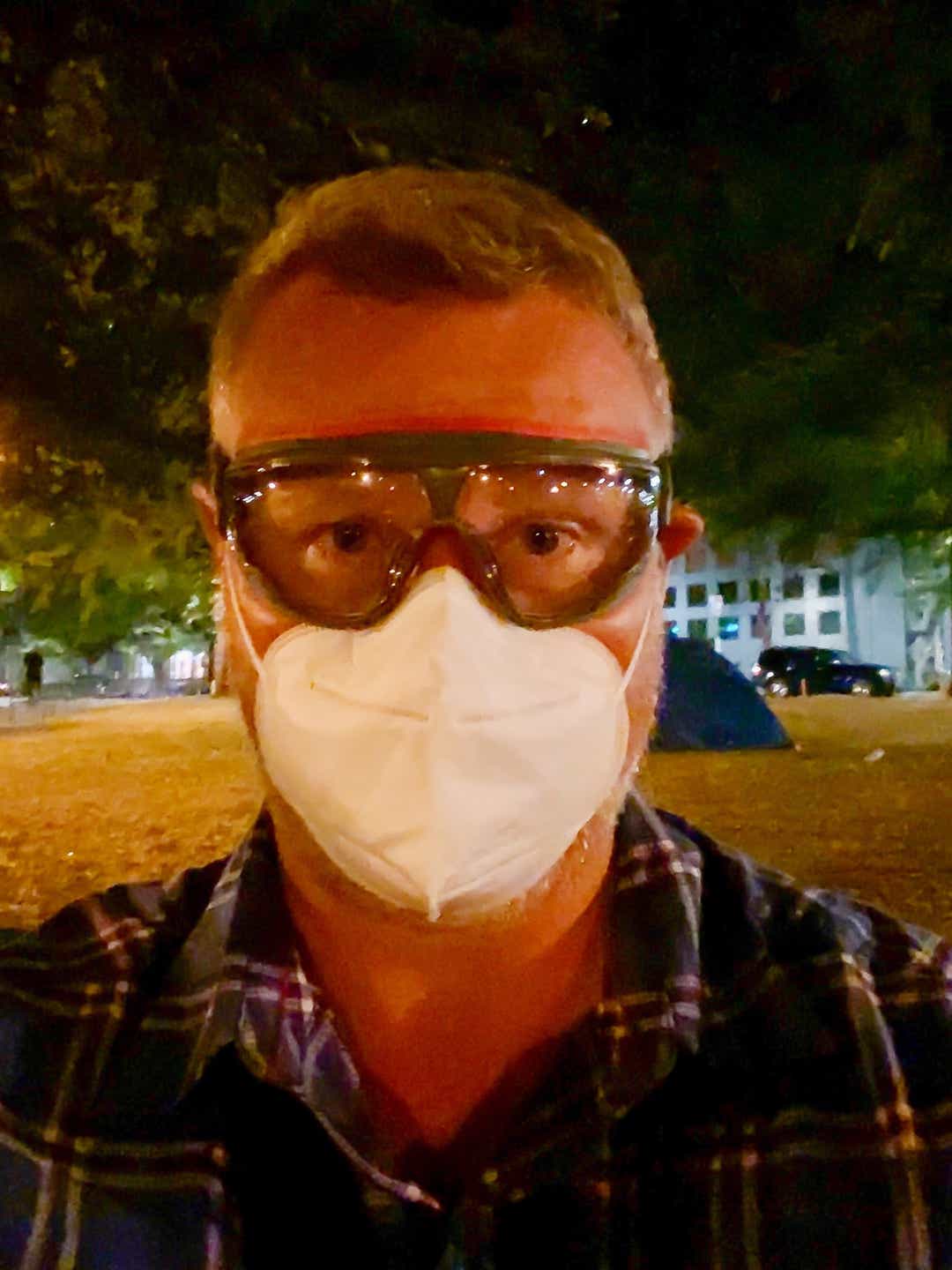

Hughes said when he's reporting, he "keeps his head on a swivel." His keeps his back toward a wall, and is constantly surveying what is coming near him.

"You have to remember that in these instances, we are not the friend of anybody," he said. "We're not on anyone's side, we're not anyone's buddy. You are just as likely to get shot with tear gas or pepper balls as you are to be punched by a protester, especially if you're in the middle of a protest, specifically identified as press, because there are many, many people within these groups who believe that large organizations like ours are part of the problem."

For that reason, many reporters, including Hughes, keep their identification tucked away until they need it. In Portland, there was an agreement that police would not specifically target journalists. So Hughes bought a yellow vest from a hardware store and stapled "PRESS" in reflective letters across the back.

He tried not to get between officers and protesters, but stay to the side. He was both reporting and photographing the scene, so his face was often in his camera's viewfinder. "I shoot, then look around. I shoot, then look around." He has been tear gassed plenty in his career, but now knows the signs of when it's time to move.

And he said he wouldn't be anywhere else.

"We're on the front lines of history right now," Hughes said. "These are events that schoolchildren will study 50 years from now.

"I really feel that responsibility to try and get it right and be accurate so that people can look back at our coverage and say, yeah, this was what happened."

The Backstory: John Lewis urged journalists, 'be a headlight, not a taillight'

The Backstory: There is more to the Frederick Douglass story. Her name is Anna Murray Douglass.

Nicole Carroll is the editor-in-chief of USA TODAY. Reach her at EIC@usatoday.com or follow her on Twitter here. Thank you for supporting our journalism. You can subscribe to our print edition, ad-free experience or electronic newspaper replica here.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de